Every so often, I scroll through educator forums or chat with colleagues, and I hear a familiar refrain: “Kids today just don’t listen.” “Their attention spans are non-existent.” “They can’t even write a full sentence anymore, it’s all TikTok captions.” The phrases vary, but the sentiment is clear: we’re witnessing a decline, a “brain rot,” a degradation of language and basic skills that feels unprecedented. But, if you look deeper, you see that this generational language panic is repeated with every generation.

As an SLP, I see these struggles firsthand. It’s easy to feel like we’re fighting a losing battle against screens, instant gratification, and a perceived societal slide. But what if these feelings, while valid, aren’t actually new? What if the “kids these days” lament is as old as the institution of schooling itself?

This question sent me down a fascinating rabbit hole into the history of education, specifically the turn of the 20th century (roughly 1890-1920). It was an era of immense change: industrialization, urbanization, mass immigration, and the rapid expansion of public schooling. And guess what? Teachers then were airing strikingly similar grievances.

Far from a silent golden age of respectful, diligent students, historical records reveal a different picture. Teachers, often young women, were facing packed classrooms of diverse learners. They battled daily with issues that sound eerily familiar. Our panic about generational language issues is definitely not new.

Generational Decline Then vs. Now: Specific Examples:

Let’s break down some of those “turn of the century” complaints and see how they mirror our present-day struggles. You might be surprised by how little the core issues have changed, proving that today’s “brain rot” in youth is not new:

The Loss of Conversation: From “Cheap Novels” to Cellphones

- Then (c. 1900): Teachers and parents feared students were wasting their minds on the era’s new, pervasive, and easily accessible media: cheap fiction novels and sensational newspapers. They worried these “over-stimulating” print materials were corrupting the youth, pulling their focus from family interaction, academic study, and proper social conversation. The concern was that constant private reading would lead to social isolation.

- Now (c. 2020): We lament that cellphones, social media, and gaming have captured student attention, leading to a decline in face-to-face social skills, difficulty maintaining eye contact, and a loss of focused conversation. The fear is that the screen is isolating students and killing their ability to communicate in depth.

- The Constant: The Loss of the Shared Social Space. Adults worry when youth attention is captured by a new, easily accessible, and unsupervised medium that pulls them away from traditional, adult-sanctioned interaction. The anxiety is identical: a new technology is diverting youth attention and killing conversation and focused thought.

The Scourge of Slang: Language Decay Myth

- Then (c. 1900): Educators constantly fought against the “corruption” of the English language through slang and regional vernacular. This informal street language and emerging youth culture were viewed as a sign of poor intellectual discipline, illiteracy, and a direct threat to proper grammar and vocabulary in the classroom.

- Now (c. 2020): We worry about “brain rot” manifested as students using acronyms, “text-speak,” and minimalist language. We view the over-reliance on AI for writing and shorthand communication as proof of intellectual laziness and a devastating decline in the ability to construct a coherent, sophisticated sentence.

- The Constant: The Linguistic Turf War. The older generation, which defines the “rules” of language, feels threatened by the rapid, creative, and efficient linguistic innovations of the youth. What one generation views as degradation, the younger often sees as efficiency, social belonging, and evolution. The adult disapproval of the change is a constant fixture of the generational divide.

The Battle for Attention: “Unruly” vs. “Distracted”

- Then (c. 1900): Teachers complained vociferously about “unruly” and defiant older boys, especially in mixed-grade rural schools, who would openly challenge authority, flirt, or cause general disruption. Maintaining order often required corporal punishment. Students struggled with the monotonous rote memorization that defined much of the curriculum.

- Now (c. 2020): We lament short attention spans, the constant pull of phones, and students who seem unable to focus on a single task for more than a few minutes. Teachers battle apathy and a perceived lack of respect.

- The Constant: The younger generation naturally resists methods and structures they find unengaging or authoritarian. Their attention is drawn to dynamic, personally relevant stimuli – whether that was pushing boundaries with a teacher or scrolling through TikTok. The expression of disengagement changes, but the root of it often remains the same: a mismatch between intrinsic motivation and imposed task. Analyzing the history of social change shows the fundamental challenge remains the same: engaging the student.

Competing Demands: “Farm Work” vs. “Side Hustles”

- Then (c. 1900): A major headache for teachers was chronic absenteeism due to child labor. Kids were pulled from school for weeks at a time to work on farms during planting/harvesting seasons or to contribute to family income in factories. Their primary focus was often outside the classroom.

- Now (c. 2020): While child labor is (thankfully) not the same issue, teachers still face students who prioritize outside commitments – part-time jobs, demanding sports schedules, extensive extracurriculars, or even gaming – over schoolwork. Their energy and focus are split.

- The Constant: Life outside school has always competed fiercely for students’ time and mental energy. The “teacher’s priority” is often just one of many, and not always the dominant one, in a young person’s life.

The “Degradation” of Language & Skills: From “Rote” to “Rot”

- Then (c. 1900): Progressive educators and frustrated teachers argued vehemently against the prevailing rote memorization model, believing it failed to teach students practical skills, critical thinking, or genuine understanding. They believed students weren’t truly learning what they needed for the modern world.

- Now (c. 2020): This is where the “brain rot” and language degradation arguments truly hit home. We worry about students’ inability to write coherently, their reliance on text-speak, AI for essays, or their struggles with complex reasoning. We hear, “They just can’t think anymore!”

- The Constant: Every generation defines “essential skills” and “proper language” by its own standards. What one era sees as practical, another sees as outdated. What one generation considers a conversational shortcut (e.g., shorthand in the early 1900s, texting abbreviations today), another deems a symptom of intellectual decay. The anxiety around changing communication styles and perceived declining rigor is a generational echo.

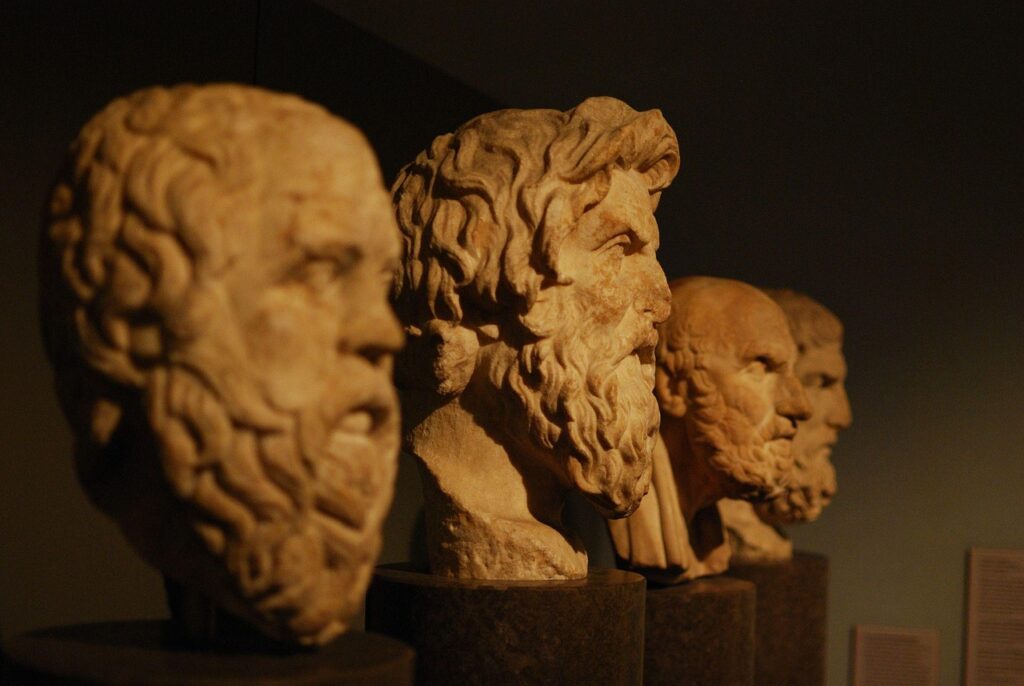

The Original Brain Rot: Luxury and Contempt for Authority

“The children now love luxury; they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show disrespect for elders and love chatter in place of exercise. Children are now tyrants, not the servants of their households. They no longer rise when elders enter the room. They contradict their parents, chatter before company, gobble up dainties at the table, cross their legs, and tyrannize their teachers.”

- Then (c. 4th Century BC): The greatest thinkers of Ancient Greece—Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle—complained extensively about the youth. While this famous viral quote is often misattributed (it was actually penned in 1907), the sentiment of generational language panic is real. Scholars even then complained about the decay of the youth. Critically, Socrates was famously executed, in part, for the crime of “corrupting the youth” by teaching them to question their elders and the established order.

- Now (c. 2020): These are nearly verbatim the complaints you hear today. Students are seen as entitled, unwilling to follow rules, glued to their phones (chatter), and disrespecting traditional structures. The modern equivalent of “corrupting the youth” is the anxiety over teaching critical race theory or complex social justice issues—anything that encourages students to question and critique the beliefs of the previous generation.

- The Constant: The Fear of the Successor. The oldest generation’s deepest fear is that the rising generation will reject the hard-won values, discipline, and institutions they built. In every era, teaching youth to think differently than the previous generation is perceived by some established adults as the ultimate act of “corruption.”

The Underlying Force behind “Brain Rot” Myth: Generational Tension

What these historical parallels underscore is not a continuous, linear decline in human intellect or student quality. Instead, they point to a fundamental, ever-present phenomenon: generational tension.

This tension isn’t about one generation being inherently “better” or “worse” than another. It’s about:

- Different Lived Experiences: Each generation grows up in a unique technological, social, and economic landscape, shaping their worldviews, priorities, and learning styles.

- Mismatched Expectations: Educators, as members of an older generation, naturally teach and assess based on the norms, skills, and values they were taught. Students, operating within their own contemporary reality, respond differently.

- The Nature of Youth: Youth, by its very nature, involves questioning, exploring, and pushing boundaries. This manifests as “unruly” behavior or “distracted” minds, depending on the era’s context.

Adapt instead of panic: Generational Language

So, the next time you feel that pang of despair about supposed “brain rot” or the state of modern education, take a deep breath. Acknowledge the very real challenges we face today – screens are powerful distractors, and mental health is a major concern. But also, take solace in knowing that you’re part of a long, distinguished lineage of educators who have felt similar frustrations.

Our job isn’t to bemoan the “decline,” but to understand the nature of this perennial generational tension. By doing so, we can shift our focus from complaining about what students aren’t to creatively finding ways to meet them where they are. We should adapt our strategies, and leverage their unique generational strengths to foster true learning.

For us as SLPs and educators, this historical context shifts our job description. Instead of fighting text-speak, we can view it as a linguistic window. We can use our expertise to bridge the gap between efficient social language and sophisticated academic language. Our goal remains the same: fostering effective communication across all contexts.

The kids aren’t “brain rotted”; they’re just kids, living in their time, and challenging us to evolve, just as kids have always done.

Want to learn more? See these posts:

- Middle School Language Development: What They Don’t Know May Surprise you!

- Beyond “Spill the Beans”: Why Teaching Idioms Needs a Modern Glow-Up

Leave your thoughts!

What historical or modern “kid complaints” resonate most with you? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Further Reading:

- https://www.pbs.org/onlyateacher/timeline.html

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/culture-magazines/1910s-education-topics-news

- https://nces.ed.gov/pubs93/93442.pdf

- https://www.rd.com/list/what-school-was-like-100-years-ago/

- https://historyhustle.com/2500-years-of-people-complaining-about-the-younger-generation/

- https://slate.com/technology/2017/08/the-19th-century-moral-panic-over-paper-technology.html